Gas, stars, metals and the surface density of star formation

I talked a bit about Sahar Rahmani’s recent project here but now that the paper has been accepted for publication, you can read it for yourself in preprint form. if you’d rather not wade through the jargon, below is my attempt to summarize the work for non-astronomers.

The paper title is “Star formation laws in the Andromeda galaxy: gas, stars, metals and the surface density of star formation” which goes a long way toward explaining what the paper is about. Let’s unpack those terms a little:

Star formation: while stars make up a pretty small percentage of the universe’s mass, they do a lot of important stuff, like providing energy to planets, performing nuclear fusion, and making the universe pretty to look at. We know that stars are still forming today because we can see massive stars nearby in our Milky Way, and our understanding of how stars works implies that massive stars don’t live very long – so they must have formed recently. It isn’t easy to understand exactly how stars form: the process takes millions of years and for some of that time is pretty well-hidden.

Star formation laws are one way we try to understand how star formation happens. The idea is to try and figure out what conditions cause new stars to form by observing other galaxies, where we can see a whole range of different conditions. `Laws’ is really a misnomer here: these are descriptive observations of how the star formation rate (that is, how fast mass is being turned into new stars) in a galaxy relates to its other properties, described below.

the Andromeda galaxy: is a neighbour to our own Milky Way and one of my favorite galaxies. It’s not an identical twin to the Milky Way, but is similar enough that it provides a good comparison. Because it is so nearby, Andromeda appears quite large on the sky compared to other galaxies. This can make studying it more difficult because lots of telescopes can only see a piece of the galaxy at once; often it takes a lot of time to gather all the necessary data.

gas, stars, metals: are the galaxy properties we looked at in this paper. New stars form out of interstellar gas so it makes sense that galaxies with more gas should make new stars faster – they do, and this has been known for quite a while. Some more recent research suggested that the mass of stars within a galaxy also affects the rate of new star formation (perhaps because their gravity affects the gas clouds), and we wanted to test this idea. The final property we looked at is the abundance of metals which in astronomer-speak means “elements heavier than helium” (so elements like carbon and oxygen as well as more usual metallic things like iron); these could affect star formation in a number of ways. For example, more metals in the interstellar gas usually means more interstellar dust, which can affect the temperature of the gas and in turn how fast it can pull together via gravity to make new stars.

the surface density of star formation: refers to the fact that, when we look at another galaxy, we don’t usually have 3-D vision. What we measure is the light coming from a given area on the sky, but in most cases we can’t tell whether the light is coming from the front, the back, or somewhere in between. So we are measuring a surface density.

What the paper is about, then, is measuring how fast new stars are forming in Andromeda, and relating that to other properties of the galaxy in order to find out what makes the star formation happen. About half of the work is the measuring part, and the other half is the relating part.

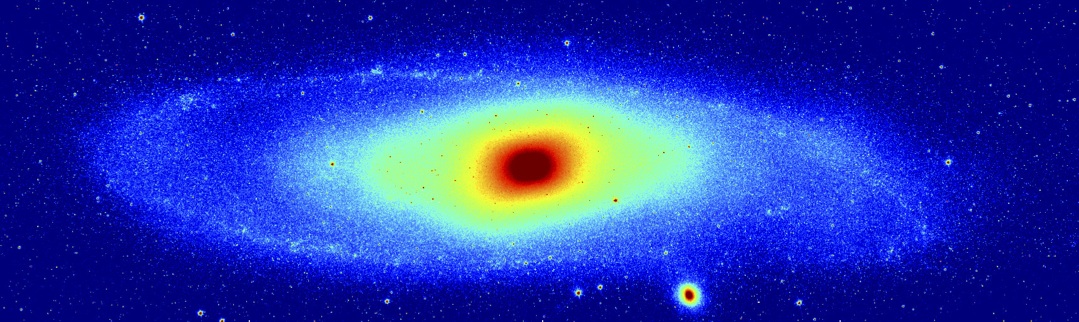

Since star formation takes so long, you can’t sit around and count the number of new stars formed in a given year. Instead you look for particular wavelengths of light that are emitted by new stars or forming stars, and using an understanding of how populations of stars together emit light, convert this light measurement into a star formation measurement. We used a couple of different ways to measure star formation in this paper: the map below shows the infrared light emitted by dust around newly-formed stars.

Measuring the amount of gas in a galaxy requires mapping the radio waves emitted by the atoms and molecules of gas between the stars. While most of this gas is hydrogen, only some of the hydrogen is easy to detect: the rest of it has to be inferred by instead detecting radio waves from carbon monoxide mixed in with the hydrogen. Measuring the mass of stars in a galaxy is not quite as tricky as measuring star formation or gas; we just take a picture with a wavelength of light that is mostly emitted by old stars (they make up most of the mass) and not absorbed by dust. The Spitzer Space Telescope’s IRAC camera works great for this.

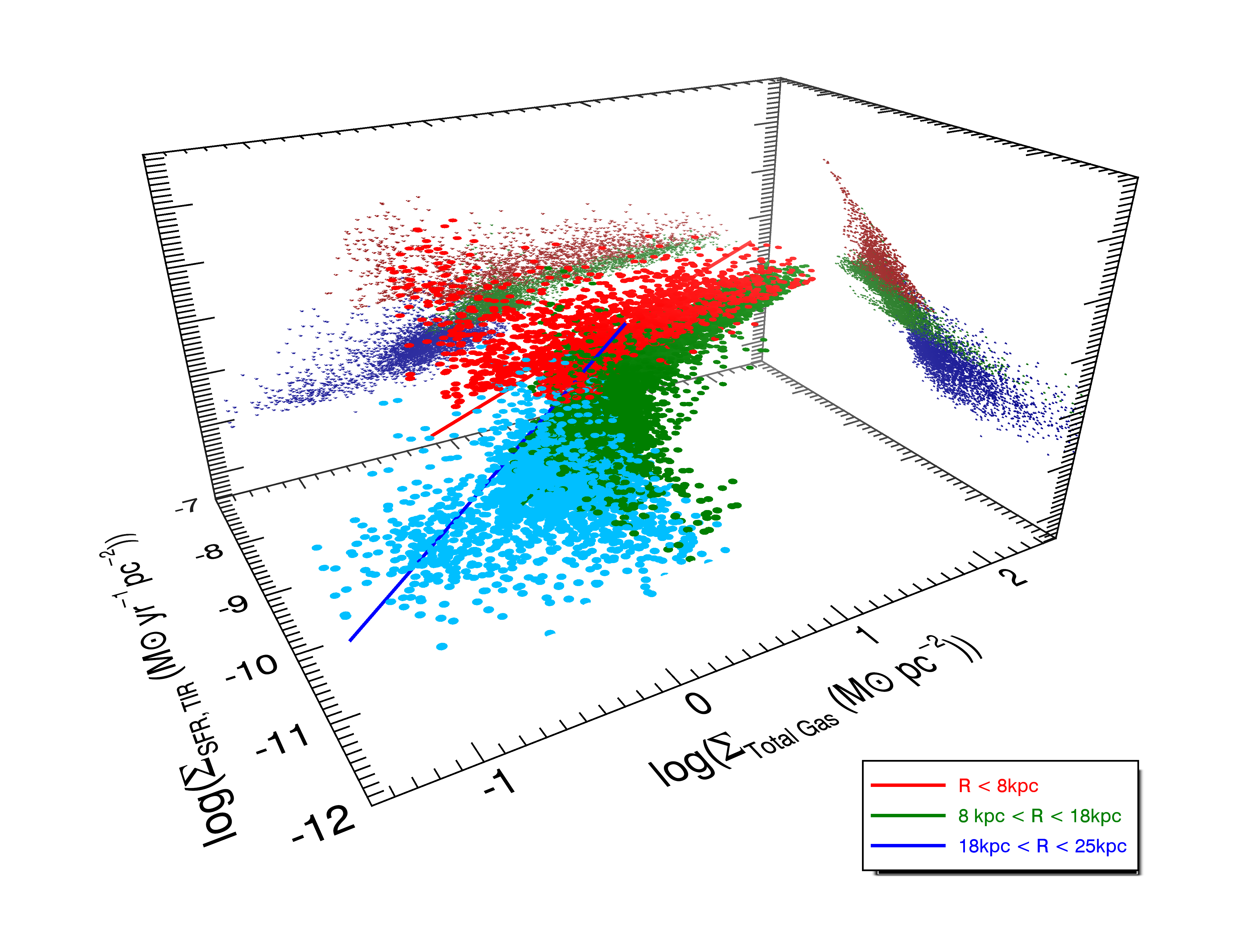

To relate all of these things together, Sahar had to learn some complicated statistics (hierarchical Bayesian analysis if you really want to know). She also had to learn how to make complicated plots, since if you want to compare 3 quantities it’s good to show them in 3 dimensions. She worked it all out though:

What this plot shows is that there is a relationship between star formation, gas, and stars, but that relationship depends on whether you are considering the centre of the galaxy (red points), middle regions (green) or outskirts (blue). The relationship doesn’t really depend on exactly how you to measure the star formation, but it does depend on the way you measure the gas and on the technical details of how you do the statistics. The final conclusion is that the stars matter: you get a better description of the star formation when you consider that it depends on both the stars and gas, not just the gas.

It is fair to say that nothing in this paper totally disrupts everything we thought we knew about star formation. Contrary to what you might think from news coverage of science, most papers are like this: small advances in knowledge which add something to what we already know. By applying new techniques and comparing them to older ones, we were able to show that the technique affects the results you get, which is always good to know. Little by little, science moves forward; we hope this paper is a small step towards better understanding how stars form.