All M31, all the time

I am spending a couple of weeks at NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics in Victoria, and am giving an informal talk today about the research projects I am working on with my students. Here’s a blog-ified summary for posterity, an updated version of the research description on my (gee-I-should-really-update-it) webpage.

I did my PhD thesis on the globular clusters of the Andromeda galaxy (M31), and although I have done research on many (probably too many) other topics, I seem to keep coming back to M31. Why? I guess it’s partly familiarity; it’s a galaxy I know really well, and I like the feeling of knowing what’s going on. But there’s also the undeniable fact that it’s the nearest big galaxy outside the Milky Way, and if you want to get a good picture of what’s going on in such galaxies, it’s a pretty good place to look.

In some work with now-completed MSc student Mitch Croley, we used spectra from the Gemini telescope to measure the abundances of heavy elements, particularly oxygen, in gas clouds located at different distances from the galaxy centre. Because oxygen is made in stars and returned to the space between stars after they die, measuring how much of it there tells you how many cycles of star-birth-and-death have happened at different places. This project is somewhere between almost-done and just-started: we thought we had finished the work, and submitted a paper to a journal, but the paper referee correctly pointed out some major flaws in the data analysis. So some of it has to be redone, but because the person who did most of the first round of work has moved on, it’s been hard to get it restarted. Lesson: document your work. And make your students document theirs.

The second project, with MSc student Dimuthu Hemachandra and cosupervisor Els Peeters, is another almost-done one. Again we are looking at stuff in the space between stars, but this time it’s large molecules containing carbon. There had been suggestions in earlier work that there was something weird about these molecules in M31, but with new data from the [Spitzer Space Telescope][http://spitzer.caltech.edu] we found that didn’t seem to be the case. We did find some interesting hints that there might be silicon-containing dust near M31’s central black hole, something that hasn’t been seen before.

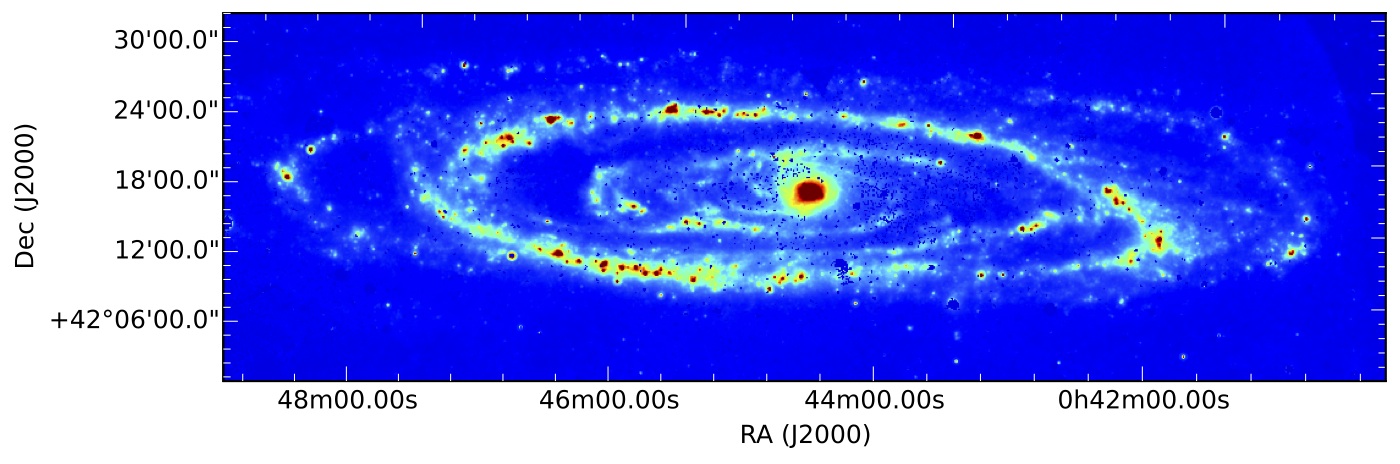

Project #3 with PhD student Sahar Rahmani, is about both the gas and the stars in M31. Sahar came up with the idea of testing various mathematical descriptions of how the rate of formation of new stars relates to both the density of gas and the density of existing stars in the galaxy. She figured out various clever tricks to map out the star formation rate, the gas, and the stellar mass, using data from at least half a dozen telescopes on the ground and in space. Sahar used some sophisticated statistical methods for comparing the datasets and made some nifty plots (below). It seems that both gas and existing stars are important; you can’t consider only one of them in predicting how many new stars a galaxy is making.

Another project focusing on M31’s stars with MSc student Masoud Rafiei-Ravandi, involves trying to trace M31’s stars as far away from the centre of the galaxy as possible. Like most galaxies, the stars are closest together in the centre and then get less dense further out. Tracing exactly how the density of stars falls off can give clues to the overall structure of the galaxy. This project used Spitzer data again, this time from the IRAC camera, which I worked on before coming to Western. There are quite a few technical things to worry about in making sure that we are tracing the galaxy itself and not the Milky Way stars in front of it or the distant galaxies behind it; some of those technical issues are things I’ve been working on this week.

The final project, by PhD student Neven Vulic with co-supervisor Sarah Gallagher, involves objects in M31 that emit X-rays. These tend to be exciting things like black holes or neutron stars that are pulling in gas and heating it up to high tempertaures. Because black holes and neutron stars are produced at the ends of the lives of massive stars, knowing where these things are, and their properties, tells us about the past history of star formation in M31. Neven has been working on analyzing all of the data taken on M31 with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. This is quite the massive job, and will result in a much more comprehensive catalog of X-ray sources in M31 than any we have now. Like some of the other projects, it’s quite technical and requires a lot of computing, but it’s almost done!

This work covers M31 in wavelengths from radio to X-rays; so far no gamma rays but maybe that should be another project. Putting all of these datasets together is a lot of fun, and a “meta-project” I am thinking about involves how to do that in a more efficient way. More on that, and on the other galaxies I do work on, in another post.