More galaxies!

Back in October, there were a number of news stories with headlines like

- “The Universe Has 10 Times More Galaxies Than Scientists Thought”,

- “We Were Very Wrong About the Number of Galaxies in the Universe”

- “Two Trillion!” –The New Hubble Estimate of the Number of Galaxies in the Universe

These stories were based on this press release which in turn describes the paper “The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and its Implications”. Two months later, I finally have time to read the paper and add my own two cents. One thing I can do immediately is translate the paper title! “Evolution” here refers to changes as the universe ages; “galaxy number density” means the number of galaxies in a given volume of space (think of a counting the number of galaxies in a gigantic cube and dividing by the volume of the cube); and “at z < 8” describes how far back into the history of the universe the measurement is being made.

Estimating the total number of galaxies in the universe is not easy to do; there are a lot of complicating factors. One is that there are more little galaxies than big ones: the big ones are easy to find and count, but the little galaxies which make up most of the population emit less light and are more difficult to see. It’s necessary to make some kind of statistical correction to account for the undetectable galaxies. Another complication is that the galaxy population has changed over time as the universe has expanded and cooled. The numbers and sizes of galaxies we see nearby aren’t necessarily representative of the history of the universe, so we have to measure the galaxy population in the past as well. Fortunately, because light from distant galaxies takes a long time to reach us, when we look at very distant galaxies, we’re looking at the universe as it was long ago - so instant time machine!

The third complication is redshift: light from distant galaxies is shifted to longer wavelengths, so the light we observe from distant galaxies is not quite the same as what we see from nearby galaxies. Again a correction has to be made. Redshift is denoted with the symbol z, so z < 8 in the paper title tells astronomers the distance to the galaxies that are being measured. In this system, 8 is a pretty big number: light leaving these galaxies did so when the universe was about 5% of its current age.

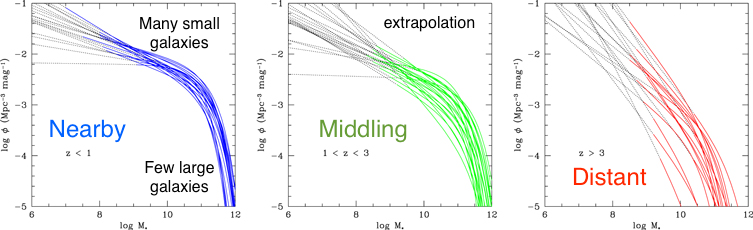

OK, so what did Conselice, Wilkinson, Duncan and Mortlock do? They combined the results from studies of the

galaxy mass function – that is, counts of the number density of galaxies as a function of mass – and its changes over time.

Most of the paper is about the technical business of how to integrate the mass function, that is, how to sum up the

number of observable galaxies and make the correction for the unobservable ones. The figure below shows the many different

mass functions that the authors looked at and how they change for galaxies at different distances.

The major finding of the paper is that the number density of galaxies has decreased as the universe has gotten older.

This is not entirely surprising –

we know that galaxies collide and merge – but this work

shows that the number of galaxies agrees with models of how this merging takes place.

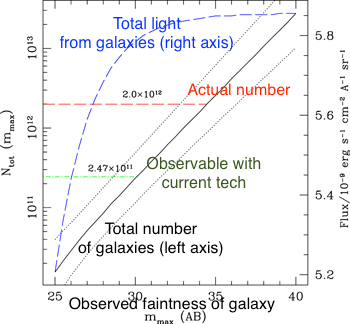

The paper summarizes this work in another figure, which shows how many galaxies can be observed as a function of how

deeply you look. They discuss the results in terms of the implications for

Olbers’ Paradox, which is something you don’t often see in

otherwise-technical papers.

The press coverage of this work didn’t always capture what I thought was interesting about it, but overall it highlighted an interesting piece of work. There will be lots more to come in this field with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, so watch this space..